- Home

- Gilbert, Morris

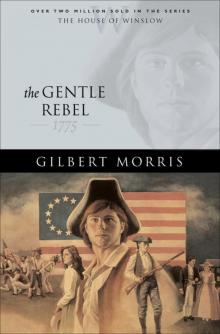

The Gentle Rebel Page 10

The Gentle Rebel Read online

Page 10

She failed to understand the anger that raced through her when she thought of the problem, but it was, she knew, getting more severe. She closed the door, went across the fresh green grass from the carriage house and into the back door. The cook, a fat black woman named House Betty (to distinguish her from Field Betty), looked up, saying, “Dey’s already havin’ brekfust, Mistuh Smith.”

It had been difficult at first, taking meals with the family, but during her first days, while giving Anne lessons, eating with the Winslows had evolved as the simplest way; now the first part of “Laddie’s” work was tutoring the girl after breakfast, then she went into town to the business.

“Laddie, I showed Papa the letter I wrote,” Anne said at once, her face beaming, “and he said it was the best he ever read!”

Charles smiled and nodded. “You’ve done wonders, Laddie—both here with Anne and at the office. I don’t see what we ever did without you.”

“It’s easy to be a good teacher,” Laddie said with a fond glance at Anne, “when you have a willing student.”

Paul spoke up. “Let me say, Laddie, that the best day’s work that Nathan here ever did in the business was to find you.”

Nathan smiled, but there was a restraint in his manner. He was subdued, and Laddie wondered if there had been some sort of problem. She asked no questions, but later in the meal, Charles said with a peculiar look in his eye, “I think I mentioned a while back that someone from our office would have to go to New York very soon to learn that new bookkeeping system from Johnson? Well, it’s got to be now. I want it set up here as soon as possible.”

“Well, I can’t go,” said both Paul and Nathan at the same instant, then paused and looked at each other.

“Neither of you want to go?” Charles said in surprise, but there was a gleam in his blue eyes. “Well, that’s too bad.” Everyone at the table, except Anne, knew that the rivalry between the cousins for Abigail had grown so heated that they stayed awake nights scheming new ways to edge one another out.

The two of them began to bicker, each trying to shove the trip off on the other, and although they were polite enough, it was obvious that they were both determined to be the one left in Boston to court Abigail.

Finally Charles raised his hand for silence. “All right, I’ll have Strake go.” He watched as they settled down, then set off his little bombshell. “But it will be a shame—because he’ll be wasted on Abigail.”

“Abigail?” Paul demanded. “What’s she got to do with a trip to New York?”

“Oh, didn’t I mention that?” Charles tried to look surprised. “Why, she’s gotten Saul and her mother to let her go for some shopping there, so we agreed that since she needed clothes and I needed someone there to learn some business, they might as well make the trip together. But it will be good for Abigail to spend some time in the company of a serious man like Strake, don’t you think so, Nathan?”

Laddie gave a sudden grin at the blank expression on Nathan’s face, but tried to look sorry when he glared balefully at her. “Why, Uncle Charles, I suppose I’ve been selfish about this whole thing.” He put a look on his face that was revoltingly pious, and added smoothly, “I suppose I could make that trip.”

Then Paul raised his eyebrows and said defiantly, “I’m going to New York, and that’s that!”

The next fifteen minutes were tense, both young men ready to fight in order to go, but in the end Charles wearied of it. He raised his voice over the strident tones of his son, who was speaking much too loudly, and said, “All right! That’s enough! I knew when this came up, there’d be no way for one of you to go—so both of you will go—and you’ll have to go along as well, Laddie.” He laughed at the surprise that crossed her face, and said, “You’ll have to do the real work while these two pound each other over the fair lady.”

“Charles, it’s not dignified!” Dorcas said.

“Love hardly ever is,” he said sourly.

“Please, Uncle Charles, I’d like to go along.”

Caleb had said nothing for so long at the table that he was usually forgotten. Now he spoke up clearly, and added, “Will it be all right? Maybe I can learn something, too.”

Charles stared at the young man, then slowly nodded, a strange expression on his face. He looks so much like Adam! “Well, it can’t do any harm. You’ll have to take the big carriage to hold all of you, but I have no objections.”

“When do we leave, Father?” Paul asked.

“You’ll pick Abigail up at ten in the morning.” He gave them a sly smile and said, “I told her you’d both be going—and that seemed to please her a great deal.”

It would! Laddie thought angrily. She’ll have them shooting each other in some fool duel before we get back! Then she had to try to console Anne, who felt left out. She took one quick look at Caleb, trying to fathom his motives, for it was one of the last things he’d have wanted to do—be away from the Sons of Liberty—but there was nothing on his face but a slight expression of satisfaction.

CHAPTER EIGHT

“A MAN IN LOVE IS BOUND TO BE A FOOL!”

“I don’t reckon Uncle Charles’s big idea is going to work, is it, Laddie?”

The front wheel of the big wagon struck a pothole just as Laddie turned to look at Caleb, and the unexpected lurch threw her heavily against Caleb, who was driving. She pulled back quickly, took a tight grip on the seat, and asked, “What big idea?”

“Why, he got this whole thing up so’s Abigail would have to choose between Nathan and Paul.” He turned to face her, a sardonic smile on his lips. “But it sure has turned out different!”

Laddie’s shoulders sagged, for the trip had been no pleasure for any of them. They had left Boston three days earlier, and the spring weather had been ideal for traveling. The roads were still heavily rutted from winter travel, but the inns had been fairly clean and the food mostly good. At their first night’s stop, however, at a villainous place called The Blue Lion, Paul had spat out what was reported to be tea, and called to the innkeeper: “Sir, if this be tea, bring me coffee. If this be coffee, bring me tea.”

And it was later at that same place that the sleeping accommodations almost caught up with Laddie. There were only two rooms; one, of course, was for Abigail, and the other for the rest of the party. All throughout the meal, Laddie’s mind was racing, and when Nathan said, “Let’s get some sleep—we’ve got a long trip tomorrow,” panic had almost taken over, but the room, they found was so small that after one look, he had said, “This bed’s too small for four. Caleb, you and Laddie will have to make out in the wagon tonight.”

As she and Caleb had settled down that night, fortified with blankets, Caleb had said, “I like this better than that dirty old room, anyway. Don’t you, Laddie? I’d just as soon camp out like this the whole trip.” Laddie had quickly agreed, and then for a long time they had lain awake, listening to the spring peepers in a nearby creek and tracing out patterns in the icy points of light the stars made against the velvet sky.

Now as Caleb drove the wagon down the final stretch of road to where the silhouette of New York could be faintly seen, Laddie looked across at his stocky figure, thinking how strange it was that she should know more of him than Nathan. Caleb had spoken wistfully of how close they had been once, and his loneliness was a sharp pain that he exposed, she knew, only to her.

Now, she picked up on his comment, saying, “I guess men in love are generally fools.”

“You got that right, Laddie!” Caleb nudged the off leader a touch with his buggy whip, and then gave a short laugh. “Don’t know what my hurry is.”

“Why’d you want to come along?” she asked.

He gave no direct answer, saying only, “Might as well be here as in Boston, I guess.”

Paul took the reins when they got to the outskirts of New York and drove to the branch office, which was located in the center of the harbor. Hiram Johnson, the manager, was a short man with a full black beard and deep-set black eyes. “Wo

n’t take more’n two or three days to learn that system.” He looked over the party and said innocently, “Reckon they’s enough of you to handle the job?”

Paul looked a little foolish, and at that instant Laddie had an idea—an answer to the ever-present problem of where she would sleep. “If you’ve got a cot here, Mr. Johnson, I could stay here around the clock. That would be quicker, wouldn’t it?”

“Sure, we can do that,” the manager agreed, and Laddie saw that both Paul and Nathan were relieved.

“I’d like to stay, too.”

Nathan stared at Caleb, and he opened his mouth to question the boy, but at that instant, Abigail said, “I really need to get settled; if you’d be so kind as to take me to the hotel.”

As Caleb and Laddie got their bags from the carriage, then watched the party drive off toward the inner city, Caleb said, “Looks like we ain’t going to be bothered much with their company, are we, Laddie?”

There was something so childish about the way the two men followed around after Abigail, glaring at each other, that Laddie muttered angrily, “Like I said, men in love are bound to be fools!”

* * *

By the third day of the visit, Nathan would have agreed totally with Laddie’s statement. He had begun well, showing up early at the office in the morning, but as the day wore on and Paul made no appearance, he grew moody. Finally at noon, he said, “Laddie, do you think you can handle this alone? I mean, I’m no clerk—so I might as well get out of your way.” Then almost without waiting for an answer, he had walked quickly out of the office and had not returned.

But he did not better himself, for if he had felt useless at the office, he felt even more out of place following around after Abigail. When the trip had come up, he had thought, Well, now I’ll be able to get her alone—away from family and everyone. But he never did that; in fact, he saw rather less of her than he had in Boston!

New York was a thriving beehive of a town, bursting at the seams, and filled with activities day and night. The streets teemed with people, including many sailors from the Royal Fleet that lay at anchor in the East River. Nathan was acutely aware that the threat of revolution lay always just beneath the surface, exactly as it had at Boston—which disturbed him. But he had little time to think about politics, for he found himself caught up in an almost frantic round of social activities led by Abigail and a group of young socialites.

They began in the mornings with tea in the lovely homes of the city, and Nathan was ill at ease. Paul and Abigail knew everyone, it seemed, and he stood on the outside looking in. He felt himself to be an outsider, a quaint colonial, a backwoodsman from Virginia, which was to some extent quite accurate. More than one pretty girl tried to draw his attention, but he was so single-minded in his pursuit of Abigail that he never noticed.

In the afternoons they prowled the streets of the Battery, took in the waxworks and the gardens, and later probed into the lower side of the city, attending a horse race and the many curiosities, peep shows, and wax museums that abounded on the lower side of Manhattan.

Then in the evenings, Abigail’s friends scheduled dances in their large homes. These affairs were like small “balls” and lasted until the early hours of the morning, and Nathan felt out of place at them as well.

On the fourth night he stood with his back against the wall in a large Dutch-style mansion, watching the dancers weave across the polished floor. He had eaten little for the past two days, and his nerves were jangling from the constant frenzied activities and from lack of sleep. He had broken his own rule and had several glasses of wine, so his head was not clear.

He had danced several times, but only once with Abigail, and as he stood there, she danced by with Paul, looking up at him, laughing, and Paul suddenly threw his head back and laughed. Behind him someone said, “Make a lovely couple, don’t they?” He glared at the overweight woman who had spoken to her equally overweight husband, then moved away.

For the next hour he grew more morose and he took several more glasses of wine from the refreshment table that groaned under the weight of food and drink. Finally, he thought, A man’s a fool to torment himself like this! He caught a glimpse of Abigail dancing with a red-coated British officer, and impulsively plunged across the crowded dance floor, bumping into several couples, until he reached them.

“Abigail, I’ve got to talk to you!” he said urgently. Both Abigail and the officer, a compact young captain with a smooth face and a pair of cold blue eyes, turned to look at him in surprise.

“Why, Nathan!” she said. “What’s the matter?”

“Come along; we can’t talk here.”

He took her arm and pulled at it, but found that the captain had anchored himself to her other arm. “You need better manners, fellow!” he said evenly. “Just you move along now.”

Nathan stared at him, but did not release the arm he held. “Soldier, we’ll get along very well without you.”

The sharp rebuke fired the cold blue eyes of the officer, and he moved toward Nathan, but Abigail said, “Edgar! Please!” She placed her hand on his arm, smiled up and said, “Excuse us, will you, please?”

“Very well—but I’ll have a word perhaps with you, sir, before you leave. We don’t need your backwoods manners in this place!”

She patted his arm, then turned, pulling Nathan after her, through a door that led into the main hallway. He followed her until she led him through a set of French doors to a small porch that looked out onto a garden.

“Now, Nathan, what’s the matter?”

“Well—” Suddenly he could say nothing, but felt foolish over his actions. He stood there in confusion, longing to say so much, yet somehow rendered speechless by her beauty.

She was beautiful—more than he had ever known! She stood there bathed in the pale moonlight that washed over her hair, and the night was so clear that he could see the curves of her cheeks, the arch of her lips. Yet coming out of the noisy ballroom into the almost holy quietness of the secluded garden had not cleared Nathan’s mind, for now, looking down at her, he felt more confused than ever.

Finally she said, “What is it, Nathan? Tell me.” And she leaned against him slightly, then raised her hand to place it on his cheek. “You’ve been so quiet lately. Are you angry with me?”

“No—but I feel like I’m out of your world, Abigail.” He took her shoulders, and the fragrance of lilacs came to him, and he whispered, “You’re so lovely, Abigail—and I feel so far away from you.”

“Don’t feel like that!” She smiled up at him, and then as he stood there, all the confusion of the trip seemed to fade. She was there, and she was lovely—so he simply leaned forward and kissed her. She did not hold back, but pressed herself against him, and the eagerness that he felt in her slim body struck him powerfully, so that he held her even tighter.

He drew back, and there was a softness in her eyes, a gentleness that she had kept hidden, and she said, “Nathan, you are . . .”

What she would have said, he never found out, for at that moment there was the sound of a door creaking, and Paul’s voice said, “Quite a pretty scene—but a little public, don’t you think?”

Nathan released Abigail and turned quickly to see him standing framed in the door. He waved a hand, and following his gesture, Nathan saw a man and a woman in a gallery across the garden watching them, and then looking to his right, several observers were standing at the large windows laughing and pointing at them.

“Nathan, you ought to have more sense!” Paul said more sharply. Then he took Abigail’s arm, saying, “I think we’d better go.”

“Take your hand off her!” Nathan said at once.

“Oh, don’t be a fool!” Paul retorted.

Nathan’s temper was even, as a rule, but once or twice in his life he had discovered that deep inside him there was the capacity for blinding rage—not just anger, much more intense than that. He had felt it once when a boy had smashed his favorite toy, and even at the age of ten he had so comp

letely lost control of himself, bellowing and striking out, that his father had been shaken.

“Nathan, you must never let yourself go like that again!” he had said with a pale face. It had happened again, however, just two years earlier, when a man who’d been half drunk had pulled a pistol and shot Nathan’s favorite dog. Nathan had no remembrance of his actions, but he’d finally come to himself with half a dozen men holding him with some difficulty, flat on his back. He had broken the man’s jaw in two places, and left his face hopelessly shattered, and the shock of it had been so great that ever since he had been careful to avoid the black rage that he knew lurked deep within him.

Now, to his horror, he felt the thing, black and ugly, rising up again, and as before it seemed to deprive him of speech, to numb his brain and thought. He heard himself give a hoarse roar, felt his hands reach out and grasp Paul, and then he heard Abigail’s frightened cry, which seemed to come from far away.

Sanity came sweeping back, and he found himself staring into the wide eyes of Paul, who seemed paralyzed by the awesome wrath that had leaped out of his tall kinsman without warning. Nathan wrenched himself away, whirled, ran headlong off the porch and across the yard, then disappeared down the street.

“I never saw him like that!” Abigail whispered. “He would have killed you!”

Paul’s hand was not quite steady as he put it on her elbow and guided her inside. He said nothing, but there was a mixture of anger and wonder in his eyes as they left, and he cast one look down the dark street where Nathan had disappeared. Yes—he would have killed me—and that’s the dark side of the Winslow blood Father’s tried to warn me of, he thought grimly.

* * *

Laddie gave a start, coming out of a sound sleep on the couch. A large hand was shaking her arm, and she opened her eyes to see Nathan, his face pale and angry, looking at her.

“Where’s Caleb?”

“Caleb?” She sat up quickly, gave a look at the second cot that had not been used across the room. She threw the light blanket off and stood up. “I guess he hasn’t come in yet.” She gave him a careful look, then asked quietly, “What’s the matter, Mr. Winslow?”

Winds of Change

Winds of Change Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters

Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters The Reluctant Bridegroom

The Reluctant Bridegroom A Bright Tomorrow

A Bright Tomorrow The Mermaid in the Basement

The Mermaid in the Basement The Saintly Buccaneer

The Saintly Buccaneer The Silent Harp

The Silent Harp The High Calling

The High Calling The Shadow Portrait

The Shadow Portrait House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman

House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman By Way of the Wilderness

By Way of the Wilderness THE HOMEPLACE

THE HOMEPLACE Last Cavaliers Trilogy

Last Cavaliers Trilogy The White Knight

The White Knight The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle

The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle A Conspiracy of Ravens

A Conspiracy of Ravens The Silver Star

The Silver Star The White Hunter

The White Hunter Race with Death

Race with Death The Hesitant Hero

The Hesitant Hero Sonnet to a Dead Contessa

Sonnet to a Dead Contessa Joelle's Secret

Joelle's Secret The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3

The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3 The Gallant Outlaw

The Gallant Outlaw A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel)

A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel) Deep in the Heart

Deep in the Heart The Final Curtain

The Final Curtain A Season of Dreams

A Season of Dreams The Beginning of Sorrows

The Beginning of Sorrows The Flying Cavalier

The Flying Cavalier Honor in the Dust

Honor in the Dust The Indentured Heart

The Indentured Heart Revenge at the Rodeo

Revenge at the Rodeo The Widow's Choice

The Widow's Choice When the Heavens Fall

When the Heavens Fall The Gentle Rebel

The Gentle Rebel One Shining Moment

One Shining Moment The Gate of Heaven

The Gate of Heaven The Captive Bride

The Captive Bride Sabrina's Man

Sabrina's Man The Jeweled Spur

The Jeweled Spur The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1)

The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1) River Queen

River Queen Dawn of a New Day

Dawn of a New Day The Holy Warrior

The Holy Warrior The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25)

The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25) The Last Confederate

The Last Confederate The Heavenly Fugitive

The Heavenly Fugitive The Royal Handmaid

The Royal Handmaid The Yellow Rose

The Yellow Rose The Sword

The Sword Daughter of Deliverance

Daughter of Deliverance Over the Misty Mountains

Over the Misty Mountains Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells

Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells The Gypsy Moon

The Gypsy Moon The Western Justice Trilogy

The Western Justice Trilogy The Union Belle

The Union Belle Deadly Deception

Deadly Deception The Final Adversary

The Final Adversary The Virtuous Woman

The Virtuous Woman Crossing

Crossing The Rough Rider

The Rough Rider Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1

Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1 The Dixie Widow

The Dixie Widow No Woman So Fair

No Woman So Fair Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga)

Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga) Guilt by Association

Guilt by Association The Wounded Yankee

The Wounded Yankee Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30)

Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30) Santa Fe Woman

Santa Fe Woman Hope Takes Flight

Hope Takes Flight The Shining Badge

The Shining Badge Angel Train

Angel Train The Crossed Sabres

The Crossed Sabres The Fiery Ring

The Fiery Ring The Immortelles

The Immortelles The Exiles

The Exiles Till Shiloh Comes

Till Shiloh Comes The Golden Angel

The Golden Angel The Glorious Prodigal

The Glorious Prodigal The River Rose

The River Rose The Unlikely Allies

The Unlikely Allies