- Home

- Gilbert, Morris

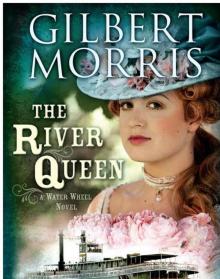

River Queen

River Queen Read online

Copyright © 2011 by Gilbert Morris

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

978-1-4336-7320-7

Published by B&H Publishing Group,

Nashville, Tennessee

Dewey Decimal Classification: F

Subject Heading: LOVE STORIES STEAMBOATS—FICTION MISSISSIPPI RIVER—FICTION

Publisher’s Note: This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. All characters are fictional, and any similarity to people living or dead is purely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 • 16 15 14 13 12 11

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

CHAPTER ONE

The snowstorm that had taken Natchez by surprise kept the temperatures well below freezing outside the family home of Charles Ashby. Fires bloomed in every room. Upstairs, in Julienne Ashby’s bedroom, the logs shifted and sent a myriad of sparks up the chimney. The heat-crackle of the wood made a cheerful sound in the room as it wafted out comforting waves of warmth. Julienne’s room was very feminine, full of flower brocades, oval-framed pictures, and mirrors. Three light, comfortable dressing chairs were set about to be both ornamental and useful. A double bed stood in the center of the room made up with clean sheets, a crisp white bolster, and a wine-colored eiderdown comforter that was pillow-thick. Set off in an angle of the room, an ornately carved mahogany washstand bore a delicate French porcelain pitcher and washbowl.

Now, however, a streak of mud went up one side of the satin-covered comforter, leading to a large dirty stain in the middle of the cover, and seated cross-legged in the middle of that stain was ten-year-old Carley Jeanne Ashby. She watched her sister Julienne as she went through the long and tedious process of dressing for a shopping excursion. Carley was a pretty girl, with long, curly red-gold hair, wide blue eyes, and a fresh peaches-and-cream complexion. She was small for her age, but she was energetic and had a strong constitution, which was a good thing since she was an incurable tomboy. Today her frilled dark-blue dress was relatively clean, as she had been wearing a heavy wool cape outside, but her pantalettes were caked with filthy mud, her hands were dirty, one of her pigtails had a dirt clod in it, and there was a streak of mud across one blooming cheek.

“Carley Jeanne Ashby,” Julienne said with mild amusement, “you are positively filthy. What on earth have you been doing? Plowing?”

Turning, Julienne huddled close to the fireplace. She had just put on her winter pantalettes and chemise—commonly pronounced “shimmy”—and shivering, she pulled on her heavy wool dressing gown again. She was a lovely woman of twenty-three, tall and slender, but with a womanly figure. Like her sister, she had inherited her gorgeous thick red-gold hair from her mother, but she had wide, very dark eyes and velvety lashes, somewhat startling with her fair hair and complexion. “Where is Tyla?” she asked herself with some irritation. “I can’t possibly lace up my corset by myself.”

But Carley ignored this and repeated loudly, “Plowing? ’Course not, ’cause I don’t have a mule. I’ve been collecting rocks. Want to see them?” When Carley Jeanne had been six years old, she had taken a straw bag from their cook, Mam Dooley, that was used for carrying vegetables from market. Carley had rarely been without the bag since then, and now it was old and frayed and permanently stained, but still she carried her “treasures” in it. These could be anything from rocks to wildflowers to bugs to fishing worms.

“No, darling, I’ll look at your rocks some other time,” Julienne answered. “So you escaped from lessons again, I take it.”

“Aunt Leah doesn’t care,” Carley said dismissively.

“You’re going to be an ignorant hooligan,” Julienne said absently, then went to the door, flung it open impatiently, and started to shout, “Ty—Oh. Here you are.”

“Here I am,” Tyla said, rolling her eyes. “I just now finished ironing these sleeves, Miss Julienne.”

“Oh, yes, I forgot. Lay the dress out, Tyla, and help me get into this corset,” Julienne ordered.

Tyla went over to Julienne’s bed and sighed as she saw the big dirty spot, and the small dirty child, in the middle of the bed.

“I’ve been collecting rocks,” Carley told her helpfully. “That’s why I’m so dirty.”

“Could you go be dirty somewhere else, please?” Tyla asked.

“No, I don’t want to. I want to watch Julienne dress. When am I going to get a shape like you, Julienne? Darcy said I look like a fence picket.”

“Little girls are supposed to look like fence pickets,” Julienne said, pulling her corset over her head. The crisscross lacings on the back hung loose. “You won’t get a womanly shape until you’re older.”

“How old?”

“A lot older. Tyla, just lay the dress on one of the chairs and come help me.”

“Yes, miss,” Tyla answered obediently. Tyla, whose name was actually Twyla, had been brought to the Ashby household when she was a newborn baby. Her grandmother, Old Mam, had been Julienne’s and her brother Darcy’s nurse. Twyla’s mother, Old Mam’s daughter, had died in childbirth, and Charles Ashby had agreed to let Old Mam bring Twyla to live with them and raise her with his own children. Julienne, at three years of age, had called her “Tyla” and the name had stuck. Tyla had grown up with the older Ashby children, but when she turned thirteen she became sixteen-year-old Julienne’s maid. Now she was a petite black woman of twenty, with a beautiful smile and a modest demeanor.

With one last regretful look at Julienne’s filthy comforter, she laid the dress on a side chair and came to tighten the laces of Julienne’s corset, while she held onto the bedpost.

“Unh,” Julienne grunted. “I knew I shouldn’t have eaten that dish of kidneys for breakfast.”

“Ecch,” Carley said. “Kidneys. You’re silly to tie yourself all up tight like that, Julienne. You’ve already got a shape.”

“When you have one, you’ll understand and you’ll tie yourself all up, too,” Julienne retorted. “What’s all this talk about a shape, anyway?”

“I was talking to my friend Denise Hopgood about it. Denise’s sister is fourteen and she doesn’t have a shape yet. We’re worried,” Carley told her solemnly.

“Carley, find something else to worry about,” Julienne said, managing a smile between grunts as Tyla yanked the corset lacings hard. Finally the corset was fastened, and Julienne had a nineteen-inch waist. Quickly Tyla picked up three petticoats, a linen, a cotton, and a woolen, pulled them over Julienne’s head and tied them around her waist. Leaning against the wall was Julienne’s hoop underskirt, collapsed into concentric rings. Tyla laid it down on the floor and Julienne stepped into the center ring. Rising, Tyla pulled the crinoline up as it ballooned out, a series of very light steel rings covered with crisp cotton, widening out to a full bell shape.

Carley watched, fascinated. “Why can’t I have one of those?”

“Because, Miss Carley, you won’t even keep your p

etticoats on if you can shuck them without your mother or your aunt noticing,” Tyla said sternly. “Whyever would you want to wear a hoop skirt?”

“I don’t want to wear it,” Carley answered impatiently. “I want to put it on and swing it back and forth and play like I’m a big bell. Or I could put it up outside, on sticks, and make a tent. Or maybe I could hang it from a tree and get under it and pretend like I’m in the clouds.”

Shocked, Tyla said, “It’s underclothes, Miss Carley. You can’t have underclothes outside flapping in the breeze for everyone to see!”

“If that’s the most shocking thing she ever does, I’ll be amazed,” Julienne said. “Oh, I do love this new outfit!”

The dress was made of chocolate brown velvet, with the wide skirt gathered so tightly that it was richly voluminous. The bodice had an open corsage, with a blouse front of ecru satin jean with tiny pleats. The high button collar folded down over a string tie of chocolate brown grosgrain. The sleeves were wide, with a wide ruffle of the ecru satin ruffle at the wrist. Her long cape-jacket was triple-tiered, of the same chocolate brown velvet with wide grosgrain trim on the three flounces. Julienne had her milliner make her a deep bonnet of the velvet, with ecru satin ruffles framing her face.

Now she sat at her dressing table, a wide oval table with a ruffled cotton tablecloth covering it, and a hinged mirror atop. Tyla began to brush Julienne’s hair and arrange it into a modest chignon so her bonnet would fit over it.

Carley studied the dress crumpled into a corner, thrown carelessly there by Julienne. It was a dark green with a flounced skirt and had a matching tartan shawl, also thrown on top of the dress. “I don’t understand why you have to change clothes, Julienne. That dress you were wearing was pretty.”

“That’s a morning dress, for receiving calls,” Julienne told her. “Now that I’m going shopping, I have to change into heavy winter underthings and an afternoon promenade dress.”

Carley grinned. “Oooh, receiving calls! Did Archie-BALD come mooning around again?”

“Carley! His name is Archibald, and you know very well that his friends call him Archie. But you’re just a little girl, and you’re supposed to call him Mr. Leggett,” Julienne scolded. “And where did you hear that? ‘Mooning around’?”

“You said it,” Carley said smartly. “I heard you tell Tyla that yesterday, when Archie-Bald called on you yesterday morning.”

“Oh. Well, you shouldn’t be eavesdropping on people’s private conversations.”

“I was sitting right here when you said it. I didn’t know I was eavesdropping. Are you going to marry Archie-Bald?”

Julienne gave a careless half-shrug. “He’d like for me to, but somehow I don’t think I could bear listening to him droning on and on forever about business. After awhile it’s somewhat like having a hum in your ear. HMMMMMMMMM.”

Carley joined in. “HMMMMMMMM. That’s Archie-Bald. Not like Etienne. Etienne’s fun. Why don’t you marry him, Julienne? He calls on you all the time too. He must like you a lot.”

Tyla finished Julienne’s hair, went to pick up her half-boots, and knelt to put them on her.

Julienne was smiling, a dreamy, private softening of her lips. “Oh, Etienne. I know he admires me, but it’s obvious that he has to marry a woman with money to support him in his chosen lifestyle, which is extravagant.”

“What’s estravagant?” Carley demanded.

“EXtravagant. It means that Etienne needs a lot of money for his clothes, his horses, his jewelry, and a fine house.”

Carley nodded. “I know, like you and Darcy. But I like Etienne. He always picks me up and swings me around and calls me cherie. And he doesn’t make me leave the parlor like Archie-Bald does when you come in. I know Etienne likes you a lot, Julienne, because at our last party I saw him kiss you when you went out into the garden—”

“What? What?” Tyla snapped, her eyes wide.

“Never mind that, Carley, you talk too much,” Julienne said hastily. “Besides, when you’re a little older you’ll learn that men like Etienne are not serious suitors. Etienne is just a tease.”

Tying up the laces on one half-boot, her head down, Tyla said quietly, “And some people may say such things about you too, Miss Julienne.”

“Why, Tyla?” Carley asked curiously. “Who’s Julienne teasing?”

“Mr. Leggett, for one,” Tyla answered. “And he’s sure not the first.”

Far from being displeased, Julienne laughed. “Tyla, you prattle on far too much about my reputation. Ever since you had that religious experience, or whatever you call it, you’ve been so holier-than-thou.”

Tyla looked as if she might argue for a moment, but then her expression softened. “I’m so sorry, Miss Julienne, I don’t mean to be that way. I just worry about you. I don’t want you to be known in town as a light woman. And I know that if you could just draw closer to the Lord Jesus, you’d understand better what I’m saying and why I worry.” She pulled the laces on the left shoe tight, and it snapped. “Oh, dear. If you’ll wait just one minute, Miss Julienne, I can pull this lace out and repair it.”

“No, no. Just take these boots and throw them away, Tyla. Go get me the other boots, the Balmorals. I should be wearing brown leather with this outfit anyway.”

Tyla looked up at her with dismay. “But Miss Julienne, these boots cost six dollars! It will be easy for me to fix this lace, and then when we go to town, I’ll get new laces.”

“No, Tyla,” Julienne said with a hint of impatience. “I am not going to town in tatters, it’s silly. I like the new Balmoral high boot style better anyway. I’ll stop by our bootmakers and order a new pair in black leather with suede uppers. As I said, just throw those away.”

With clear hesitation Tyla unlaced the other boot, then stood slowly, staring down at them. They were ankle boots, made of the finest, softest leather, with a small heel.

Eyeing her, Julienne asked, “Do you want them? If they fit, of course you can have them, Tyla. Now, hurry, please, I know Father is getting impatient, waiting for me.”

Tyla hurried out of the bedroom and Julienne turned back to the mirror to pat her hair. Soon Tyla returned with the Balmoral boots, which had a higher upper that reached to mid-shin. Kneeling again, she put them on Julienne, then stood and fluffed out her wide skirts.

“Thank you, Tyla, now why don’t you go and get your hat and cloak.”

Tyla left again and Carley asked, “Why doesn’t Tyla have to change clothes to go shopping? She’s still wearing the same dress she’s had on all day.”

“She’s just a servant, Carley, they’re not like us.” Julienne came over to the bed and reached down to take Carley’s hand. “Come on up—Oh, Carley, your hand is freezing! Why, your feet aren’t just dirty, they’re wet!”

“I know. I’m cold.”

“Silly girl. Anyone else would catch their death. Oh, Tyla, Carley is chilled through and through. Please go get Libby and tell her that Carley’s got to have a hot bath. Then come on out. By that time the carriage will be ready.”

NATCHEZ, MISSISSIPPI, IN THIS year of 1855, was the oldest town on the Mississippi River, and could arguably be said to be the most important port on that major artery of American commerce. In the eighteenth century Natchez was the starting point of the Natchez Trace, the old Indian path that led from this city on the river all the way up to Nashville, Tennessee, and the Big Muddy was the cause of all of that traffic. Men from all over the Ohio Valley transported their goods on flatboats to Natchez, sold everything including their rough rafts for lumber, and took the Trace back to their homes, either walking or by wagon. The little town of Natchez began to grow as the port commerce increased, and all of the merchants that bought and sold from the “Kaintocks,” as they called the flatboat men, prospered. They began to cultivate the little outpost of Natchez into a tidy, well-or

dered middle-class merchant town.

Later, when Robert Fulton invented his steam-powered boat, and through hybridization, cotton transformed from a hard-to-grow crop in the South to King Cotton, Natchez suddenly turned into a gracious, elegant city for rich planters, who built block after block of fine Greek Revival mansions on the high bluffs above the river. By 1855 the population of Natchez was about five thousand, so it was dwarfed by the huge sprawling cities of New York, Baltimore, and Boston; but Natchez had more millionaires by percentage than any other city in America. Natchez was a lovely small city, well-manicured and orderly, and it was strictly for the rich.

The merchant district reflected this refined strata of society, too. As Julienne looked out the window of their fine brougham carriage, she was satisfied to see that all of the sidewalks had been swept of snow, and were immaculate. The seven-block stretch of Main Street that held the shops consisted mainly of dignified brick establishments, with sparkling windows and tasteful displays.

“Father, I have to go to my dressmaker’s, Mrs. Fenner’s, my milliner’s, my shoemaker’s, my glover’s, and, and, where else, Tyla? I forget,” Julienne said.

“Confectioner’s,” Tyla prompted her. “Remember, that’s the only way you could get Miss Carley into a hot bath. You promised her you’d get her some candy.”

“Yes, confectioner’s. What about you, Father? Where are you going?”

Charles Ashby, seated across from them, looked at Julienne and frowned. He was a handsome man, with thick silver hair and patrician features, tall and with a dignified, erect posture. “I have to go to the bank and see Preston Gates.”

“Again?” Julienne said with exasperation. “Papa, you’re always so upset after you meet with him. Why don’t you two just exchange letters or something?”

“Julienne, I keep trying to tell you that handling our finances is not something you can manage by just exchanging polite notes. And why are you going on this shopping excursion? Didn’t you just have half a dozen new dresses delivered yesterday?”

Winds of Change

Winds of Change Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters

Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters The Reluctant Bridegroom

The Reluctant Bridegroom A Bright Tomorrow

A Bright Tomorrow The Mermaid in the Basement

The Mermaid in the Basement The Saintly Buccaneer

The Saintly Buccaneer The Silent Harp

The Silent Harp The High Calling

The High Calling The Shadow Portrait

The Shadow Portrait House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman

House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman By Way of the Wilderness

By Way of the Wilderness THE HOMEPLACE

THE HOMEPLACE Last Cavaliers Trilogy

Last Cavaliers Trilogy The White Knight

The White Knight The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle

The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle A Conspiracy of Ravens

A Conspiracy of Ravens The Silver Star

The Silver Star The White Hunter

The White Hunter Race with Death

Race with Death The Hesitant Hero

The Hesitant Hero Sonnet to a Dead Contessa

Sonnet to a Dead Contessa Joelle's Secret

Joelle's Secret The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3

The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3 The Gallant Outlaw

The Gallant Outlaw A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel)

A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel) Deep in the Heart

Deep in the Heart The Final Curtain

The Final Curtain A Season of Dreams

A Season of Dreams The Beginning of Sorrows

The Beginning of Sorrows The Flying Cavalier

The Flying Cavalier Honor in the Dust

Honor in the Dust The Indentured Heart

The Indentured Heart Revenge at the Rodeo

Revenge at the Rodeo The Widow's Choice

The Widow's Choice When the Heavens Fall

When the Heavens Fall The Gentle Rebel

The Gentle Rebel One Shining Moment

One Shining Moment The Gate of Heaven

The Gate of Heaven The Captive Bride

The Captive Bride Sabrina's Man

Sabrina's Man The Jeweled Spur

The Jeweled Spur The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1)

The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1) River Queen

River Queen Dawn of a New Day

Dawn of a New Day The Holy Warrior

The Holy Warrior The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25)

The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25) The Last Confederate

The Last Confederate The Heavenly Fugitive

The Heavenly Fugitive The Royal Handmaid

The Royal Handmaid The Yellow Rose

The Yellow Rose The Sword

The Sword Daughter of Deliverance

Daughter of Deliverance Over the Misty Mountains

Over the Misty Mountains Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells

Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells The Gypsy Moon

The Gypsy Moon The Western Justice Trilogy

The Western Justice Trilogy The Union Belle

The Union Belle Deadly Deception

Deadly Deception The Final Adversary

The Final Adversary The Virtuous Woman

The Virtuous Woman Crossing

Crossing The Rough Rider

The Rough Rider Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1

Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1 The Dixie Widow

The Dixie Widow No Woman So Fair

No Woman So Fair Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga)

Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga) Guilt by Association

Guilt by Association The Wounded Yankee

The Wounded Yankee Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30)

Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30) Santa Fe Woman

Santa Fe Woman Hope Takes Flight

Hope Takes Flight The Shining Badge

The Shining Badge Angel Train

Angel Train The Crossed Sabres

The Crossed Sabres The Fiery Ring

The Fiery Ring The Immortelles

The Immortelles The Exiles

The Exiles Till Shiloh Comes

Till Shiloh Comes The Golden Angel

The Golden Angel The Glorious Prodigal

The Glorious Prodigal The River Rose

The River Rose The Unlikely Allies

The Unlikely Allies