- Home

- Gilbert, Morris

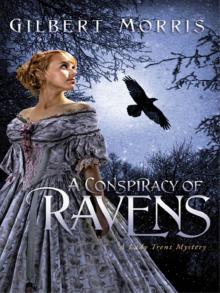

A Conspiracy of Ravens

A Conspiracy of Ravens Read online

A CONSPIRACY OF

RAVENS

OTHER NOVELS BY GILBERT MORRIS INCLUDE

The Lady Trent Mysteries:

The Mermaid in the Basement

The Creole Series

The Singing River Series

The House of Winslow Series

The Lone Star Legacy Series

Visit your online bookstore for a complete

listing of Gilbert’s books.

© 2008 by Gilbert Morris

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc. titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Publisher’s Note: This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. All characters are fictional, and any similarity to people living or dead is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morris, Gilbert.

A conspiracy of ravens / Gilbert Morris.

p. cm. — (A Lady Trent mystery ; bk. 2)

ISBN 978-1-59554-425-4 (pbk.)

1. Aristocracy (Social class)—England—Fiction. 2. Women private investigators—England—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3563.O8742C58 2008

813’.54—dc22

2008024162

Printed in the United States of America

08 09 10 11 RRD 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

ONE

October, the harbinger of winter, had fallen upon England. A cold, blustery day swept across London and the many houses that bordered the city itself. Lady Serafina Trent stared out the window, and the gloom of the day dampened her spirit. The enormous oaks seemed to be spectres raising skeletal limbs toward the sky. She was a striking woman of twenty-seven with strawberry blonde hair and violet eyes. Her face was squarish, and her mouth had a sensuous softness. She was not a woman who paid a great deal of attention to her appearance, her beauty naturally elegant.

As she looked out over the grounds, a fleeting memory came to her as she thought of how she had come, as a young bride, to Trentwood House. She remembered the joy and the anticipation that had been hers when she had married Charles Trent, but then a trembling, not caused by the temperature, shook her. She thought of her husband now dead and buried in the family cemetery and then forced the thought away.

Serafina’s eyes lingered on the grounds of Trentwood, the ancestral estate of the Trents, but now the grass was a leprous grey, the trees had dropped their leaves, and the death of summer took away the beauty of the world. Serafina suddenly turned and, with a quick movement, walked away from the window and toward the large table where her son, David, sat in a chair made especially for him. The blaze in the fireplace sent out its cheerful popping and cracking, and myriads of fiery sparks flew upward through the chimney in a magic dance.

The heat radiated throughout the room as Serafina took a seat beside her son. She glanced around, and once again old memories came—but this time more pleasant ones. This was the room that she had persuaded Charles to give her as a study, and it was lined with the artifacts of the anatomy trade. A grinning skeleton, wired together, stood at attention across the room. She and her father had built it when she was only thirteen, and after her marriage it had come with her to Trentwood. Charles had laughed at her, saying, “You love death more than life, Serafina.”

Once again the bitter memory of her marriage to Charles Trent brought a gloom to Serafina. She quickly scanned the room, noting the familiar bookshelves stuffed with leather-bound books, the drawings of various parts of the human anatomy on the walls, the stuffed animals that she and her father had dissected and put back together again. A table stretched the length of one wall, covered with vials, glasses, and containers, and she remembered how she had labored in the world of chemistry during her early years at Trentwood.

“Mum, I can’t do these fractions!”

Serafina smiled and put her arm around David. At the age of seven he had some of her looks—her fair hair complemented by dark blue eyes that had just a touch of aquamarine. He was small, but there was the hint of a tall frame to come.

“Of course you can, David.”

“No, I can’t,” David complained, and as he turned to her, she admired the smooth planes of his face, thinking what a handsome young man he would be as he grew older. She saw also that instead of figures on the sheet of paper before him, he had drawn pictures of strange animals and birds. He had a gift for drawing, she knew, but now she shook her head saying, “You haven’t been working on fractions. You’ve been drawing birds.”

“I’d rather draw birds than do these old fractions, Mum.”

Serafina had learnt from experience that David had inherited neither her passion for science nor the mathematical genes of his grandfather, Septimus. He was intrigued more by fanciful things than numbers and hard facts, which troubled Serafina.

“David, if you want to subtract a fraction from a whole number, you simply turn one of the whole numbers to a fraction. You change this number five to four, and that gives you a whole number. Now you want to subtract one-fourth from that. How many fourths are there in a whole number?”

“I dunno, Mum.”

Serafina shook her head slowly and insisted, “You must learn fractions, David.”

“I don’t like them.”

David suddenly gave her an odd, secretive look that she knew well. “What are you thinking, Son?”

“May I show you something I like?”

Serafina sighed. “Yes, I suppose you may.”

David jumped up and ran to the desk. He opened a drawer and took something out. It was, Serafina saw, a book, and his eyes were alight with excitement when he showed it to her. “Look, it’s a book about King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.”

Serafina took the book and opened it. On the first page she read, “To my friend David,” and it was signed “Dylan Tremayne.” “Dylan gave you this book?”

“Yes. Ain’t it fine? It was a present, and he gave me his picture too.” David reached over and pulled an image from between the pages of the book. “Look at it, Mum. It looks just like him, don’t it now?”

Serafina stared at the miniature painting of Dylan Tremayne, and, as always, she was struck by the good looks of the man who had come to play such a vital part in her life. She studied the glossy black hair with the lock over the forehead as usual, the steady wide-spaced and deep-set eyes, and then the wedge-shaped face, the wide mouth, the mobile features. With those beautiful eyes, he’s almost too handsome to be a man.

The thought touched her, and she remembered how only recently it had been Tremayne who had helped her to free her brother, Clive, from a charge of murder. She remembered how at first she had resented Tremayne for everything that he was, all which ran against the grain for the Viscountess of Radnor. Whereas she herself was logical, scientific, and reasonable, Dylan was fanciful, filled with imagination, and a fervent Christian, believing adamantly that miracles were not a thing of the past. She was also disturbed by the fact that although she had given up on romance long ago, she had felt the stirrings of attraction for this actor who was so different from everything that she believed.

She had tried to think of some way to curtail Dylan’s influence on David, for she felt it was unhealthy—but it was very difficult. David was wild about Dylan, who spent a great deal of time with him, and Serafina was well aware that her son’s affection for Tremayne was part of his latent desire for a father.

Firmly Serafina said, “David, this book isn’t true. It’s made up, a storybook. It’s not like a dictionary where words mean certain things. It’s not like a book of mathematics where two plus two is always four. It isn’t even like a history book when it gives the date of a famous person’s birth—those are facts.”

David listened but was restless. Finally he interrupted by saying, “But, Mum, Dylan says these are stories about men who were brave and who fought for the truth. That’s not bad, is it?”

“No, that’s not bad, but they’re not real men. If you must read stories about brave men, you need to read history.”

“Dylan says there was a King Arthur once.”

“Well, Dylan doesn’t know any such thing. King Arthur and his knights are simply fairy tales, and you’d do well to put your mind on things that are real rather than things that are imaginary.” But even as Serafina spoke, she saw the hurt in David’s eyes, and her own heart smoldered. “We’ll talk about it later,” she said quickly. “Are you hungry?”

“Yes!”

“You’re always hungry.” Serafina laughed and hugged him.

“Dylan says he’s going to come and see me today. Is that all right?”

“Yes, I suppose so. Come along now. Let’s go see what Cook has made for us.”

The dining room was always a pleasure to Serafina, and as she entered it she ran her eyes over it quickly. The table and sideboard were Elizabethan oak, solid and powerful, an immense weight of wood. The carved chairs at each end of the table had high backs and ornate armrests. The dark green curtains were pulled back now, and pictures adorned the walls. It was a gracious room and very large; the table was already laden with rich food set out on exquisite linen. Silver gleamed discreetly under chandeliers fully lit to counteract the gloom of the day.

“You’re late, Daughter. You missed out on the blessing.”

The speaker, Septimus Isaac Newton, at the age of sixty-two managed to look out of place in almost any setting. He was a tall, gangling man over six feet with a large head and hair that never seemed to be brushed as a result of his running his hand through it. His sharp eyes were a warm brown and held a look of fondness as he said, “David, I’m about to eat all the food.”

David laughed and shook his head. “No, you won’t, Grandfather. There’s too much of it.”

Indeed, the table was covered with sandwiches, many of them thinly sliced cucumber on brown bread. There were cream cheese sandwiches with chopped chives and smoked salmon mousse. White bread sandwiches flanked these. Smoked ham, eggs, mayonnaise with mustard and cress, and grand cheeses of all sorts complemented the meal as did scones, fresh and still warm with plenty of jams and cream, and finally cake and exquisite French pastries. Serafina led David to the chair, and James Barden, the butler, helped her into her own, then stepped back to watch the progress of the meal.

As Serafina helped David pile food onto his plate, she listened to her father, who chose mealtime to announce the scientific progress taking place in the world.

“I see,” Septimus said, “that London architects are going to enlarge Buckingham Palace to give it a south wing with a ballroom a hundred and ten feet long.”

“That’s as it should be. The old ballroom is much too small.”

The speaker was Lady Bertha Mulvane, the widow of Sir Hubert Mulvane and the sister of Septimus’s wife, Alberta. She was a heavyset woman with blunt features and ate as if she had been starved.

“I’d love to go to a ball there,” Aldora Lynn Newton said. She was a beautiful young girl with auburn hair flecked with gold, large well-shaped brown eyes, and a flawless complexion. An air of innocence glowed from her, though she would never be the beauty of her older sister. By some miracle of grace, she had no resentment toward Serafina.

Lady Bertha shook her head. “If you don’t choose your friends with more discretion, Dora, I would be opposed to letting you go to any ball.”

Aldora gave her aunt a half-frightened look, for the woman was intimidating. “I think my friends are very nice.”

“You have no business letting that policeman call on you, that fellow Grant.”

Indeed, Inspector Matthew Grant had made the acquaintance of the Newton family only recently. He had been the detective in charge of the case against Clive Newton. After the case was successfully solved, and the murderer turned out to be the superintendent of Scotland Yard, it had been assumed that Grant would take the superintendent’s place. And Bertha Mulvane would be happy enough to receive him as Superintendent Grant.

Serafina could not help saying, “Inspector Grant was invaluable in helping get Clive out of prison.”

“He did little enough. It was you and that actor fellow who did all the work solving that case.”

“No, Inspector Grant’s help was essential,” Serafina insisted. She saw Lady Mulvane puff up and thought for an instant how much her aunt looked like an old, fat toad at times. She saw also that her aunt had taken one of the spoons and slipped it surreptitiously into her sleeve. “It’s one thing to entertain the superintendent of Scotland Yard, but a mere policeman? Not at all suitable!”

Septimus said gently, “Well, Bertha, that was a political thing. Inspector Grant should have gotten the position, but politics gave it to a less worthy man.”

Lady Bertha did not challenge this but devoured another sandwich. She ate, not with enjoyment, but as if she were putting food in a cabinet somewhere to be eaten at a future time.

Serafina’s mother, Alberta, was an attractive woman with blonde hair and mild blue eyes. She was getting a little heavier now in her early fifties, but had no wrinkles on her smooth face. Her hands showed the rough, hard upbringing she’d had, for she came from a poor family. Septimus had not been rich when they had met, and she had pushed him into becoming a doctor and later into the research that had made him wealthy and famous. “Perhaps Bertha is right, Aldora.”

“Of course I’m right!” Bertha snapped. “And you, Serafina, I’d think you’d finally gotten some common sense.”

“I’m glad to hear you think so, Aunt. What brings you to this alarming conclusion?” Serafina smiled, noting that her aunt had slipped one of the silver saltshakers into the large sleeve of her coat. She well knew that Bertha Mulvane’s own house was furnished with items that had somehow mysteriously disappeared from Trentwood House.

“Why, the fact that you have a suitor who’s worthy of you.”

“I’m not aware that I had such a suitor.”

“Now don’t be foolish, Serafina. Sir Alex Bolton is so handsome, and he has a title.”

Serafina shook her head, picked up a cheese sandwich, and took a bite of it. “He’s not calling on me. I danced with him once at a ball last week.”

“But he’s coming to dinner next week,” Alberta said, a pleased expression on her face. “And, of course, I know that he’s coming to see you.”

“Oh, he’d be such a catch!” Bertha exclaimed.

Septimus looked up from his paper. “He’s poor as a church mouse,” he said firmly. “He lo

st most of his money in bad investments and gambling.”

“Oh, you’re wrong, Septimus,” Bertha said. “He owns a great plantation in Ireland.”

“I’ve heard he owns some forty acres of bog land, good for nothing,” Septimus said, then he turned to his grandson and smiled. “David, what are you going to do today?”

“Dylan’s coming. We’re going to trap some rabbits. He knows how to snare them.”

Bertha’s face was the picture of disgust. Her neck seemed to swell, and she barely spat out the words. “I have no doubt he’s a poacher.” She turned and said, “I would think you might choose your son’s companions more carefully, Serafina.”

Serafina said calmly, “You didn’t object to Dylan when he was helping me get Clive out of a murder charge.”

Since Bertha had no defense for this, she left the room in a huff. David leaned over and whispered, “She stole a spoon, Mum.”

“I know. Just don’t pay any attention to her, David.”

The driver, a small red-faced man with oversized hands, pulled his horse up, and the hansom cab stopped. Dylan leapt out and tossed the driver a shilling, which he caught adeptly.

“Why, thank you, suh. Shall I wait fer you?”

“No, I’m not sure how long I’ll be.”

The driver did not look like one who would attend plays, but he surprised Dylan by saying, “I seen you in a play. ‘Hamlet’ you wuz called. You wuz great in that play.”

“Why, thank you, Asa.”

“Wot are you in now?”

“At the moment nothing. I’m thinking about retiring.”

“No, sir, you mustn’t do that,” the cabby insisted. “You’d be depriving folks of sumfing good.”

Dylan laughed. “Not really.” He reached into his pocket, drew out a notepad, and wrote something on it quickly. “Give this to the fellow who takes tickets at the Old Vic tonight. It’ll get your whole family in to see the play.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Dylan nodded and turned to the door. He ascended the steps and reached out for the knocker when the door opened and David came running out. “Hello, Dylan. Let’s go catch rabbits.”

Winds of Change

Winds of Change Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters

Fallen Stars, Bitter Waters The Reluctant Bridegroom

The Reluctant Bridegroom A Bright Tomorrow

A Bright Tomorrow The Mermaid in the Basement

The Mermaid in the Basement The Saintly Buccaneer

The Saintly Buccaneer The Silent Harp

The Silent Harp The High Calling

The High Calling The Shadow Portrait

The Shadow Portrait House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman

House of Winslow 14 The Valiant Gunman By Way of the Wilderness

By Way of the Wilderness THE HOMEPLACE

THE HOMEPLACE Last Cavaliers Trilogy

Last Cavaliers Trilogy The White Knight

The White Knight The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle

The Creole Historical Romance 4-In-1 Bundle A Conspiracy of Ravens

A Conspiracy of Ravens The Silver Star

The Silver Star The White Hunter

The White Hunter Race with Death

Race with Death The Hesitant Hero

The Hesitant Hero Sonnet to a Dead Contessa

Sonnet to a Dead Contessa Joelle's Secret

Joelle's Secret The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3

The River Palace: A Water Wheel Novel #3 The Gallant Outlaw

The Gallant Outlaw A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel)

A Man for Temperance (Wagon Wheel) Deep in the Heart

Deep in the Heart The Final Curtain

The Final Curtain A Season of Dreams

A Season of Dreams The Beginning of Sorrows

The Beginning of Sorrows The Flying Cavalier

The Flying Cavalier Honor in the Dust

Honor in the Dust The Indentured Heart

The Indentured Heart Revenge at the Rodeo

Revenge at the Rodeo The Widow's Choice

The Widow's Choice When the Heavens Fall

When the Heavens Fall The Gentle Rebel

The Gentle Rebel One Shining Moment

One Shining Moment The Gate of Heaven

The Gate of Heaven The Captive Bride

The Captive Bride Sabrina's Man

Sabrina's Man The Jeweled Spur

The Jeweled Spur The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1)

The Honorable Imposter (House of Winslow Book #1) River Queen

River Queen Dawn of a New Day

Dawn of a New Day The Holy Warrior

The Holy Warrior The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25)

The Amazon Quest (House of Winslow Book #25) The Last Confederate

The Last Confederate The Heavenly Fugitive

The Heavenly Fugitive The Royal Handmaid

The Royal Handmaid The Yellow Rose

The Yellow Rose The Sword

The Sword Daughter of Deliverance

Daughter of Deliverance Over the Misty Mountains

Over the Misty Mountains Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells

Three Books in One: A Covenant of Love, Gate of His Enemies, and Where Honor Dwells The Gypsy Moon

The Gypsy Moon The Western Justice Trilogy

The Western Justice Trilogy The Union Belle

The Union Belle Deadly Deception

Deadly Deception The Final Adversary

The Final Adversary The Virtuous Woman

The Virtuous Woman Crossing

Crossing The Rough Rider

The Rough Rider Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1

Rosa's Land: Western Justice - book 1 The Dixie Widow

The Dixie Widow No Woman So Fair

No Woman So Fair Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga)

Appomattox Saga Omnibus 2: Three Books In One (Appomatox Saga) Guilt by Association

Guilt by Association The Wounded Yankee

The Wounded Yankee Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30)

Beloved Enemy, The (House of Winslow Book #30) Santa Fe Woman

Santa Fe Woman Hope Takes Flight

Hope Takes Flight The Shining Badge

The Shining Badge Angel Train

Angel Train The Crossed Sabres

The Crossed Sabres The Fiery Ring

The Fiery Ring The Immortelles

The Immortelles The Exiles

The Exiles Till Shiloh Comes

Till Shiloh Comes The Golden Angel

The Golden Angel The Glorious Prodigal

The Glorious Prodigal The River Rose

The River Rose The Unlikely Allies

The Unlikely Allies